Many tiny moons came together to form moon, simulations suggest

The moon is made of moons, new simulations suggest. Instead of a single colossal collision forming Earth’s cosmic companion, researchers propose that a series of medium to large impacts created mini moons that eventually coalesced to form one giant moon.

This mini-moon amalgamation explains why the moon has an Earthlike chemical makeup, the researchers propose January 9 in Nature Geoscience.

“I think this is a real contender in with the other moon-forming scenarios,” says Robin Canup, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., who was not involved in the new work. “This out-of-the-box idea isn’t any less probable — and it might be more probable — than the other existing scenarios.”

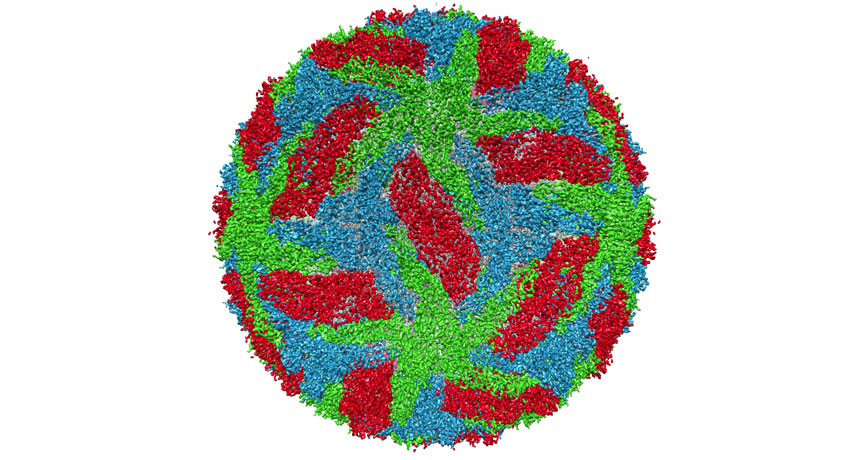

A collision between Earth and a Mars-sized object called Theia around 4.5 billion years ago is the current leading candidate for how the moon formed. This impact would have been a glancing blow rather than a dead-on collision, with most of the resulting building materials for the moon coming from Theia. But the moon and Earth are compositional dead ringers for one another, casting doubts on a mostly extraterrestrial origin of lunar material and thus the single impact explanation.

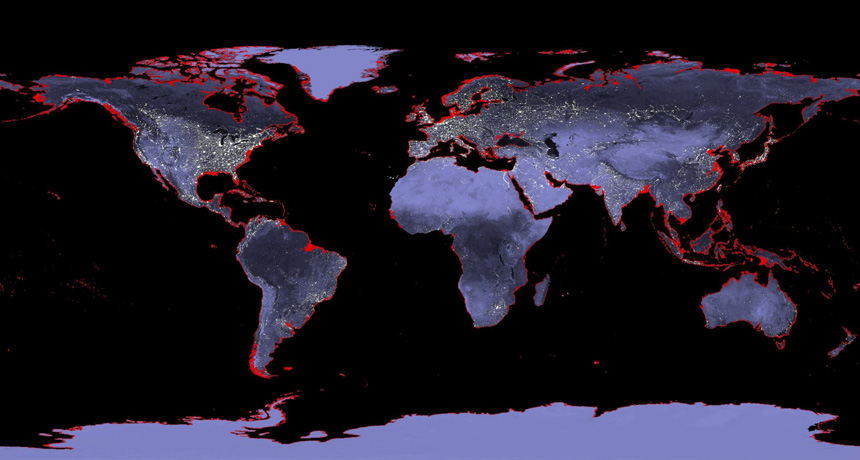

Planetary scientist Raluca Rufu of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, and colleagues dusted off a decades-old, largely disregarded hypothesis that the moon instead formed from multiple impacts. In this scenario, the early Earth was hit by a series of objects a hundredth to a tenth of Earth’s mass. Each impact could have created a disk of debris around Earth that assembled into a moonlet, the researchers’ simulations show. Over tens of millions of years, about 20 moonlets could have ultimately combined to form the moon.

Multiple impacts help explain why Earth and the moon are chemically similar. For example, each impact may have hit Earth at a different angle, excavating more earthly material into space than a singular impact would.

The single impact hypothesis has about a 1 to 2 percent chance of yielding the right lunar mix based on the makeup of potential impactors in the solar system. In the researchers’ simulations, the multiple impact scenario is correct tens of percent of the time. Further investigation of the interiors and composition of the Earth and moon, the researchers say, should reveal whether this explanation is correct.