By 2100, damaged corals may let waves twice as tall as today’s reach coasts

A complex coral reef full of nooks and crannies is a coastline’s best defense against large ocean waves. But coral die-offs over the next century could allow taller waves to penetrate the corals’ defenses, simulations suggest. A new study finds that at some Pacific Island sites, waves reaching the shore could be more than twice as high as today’s by 2100.

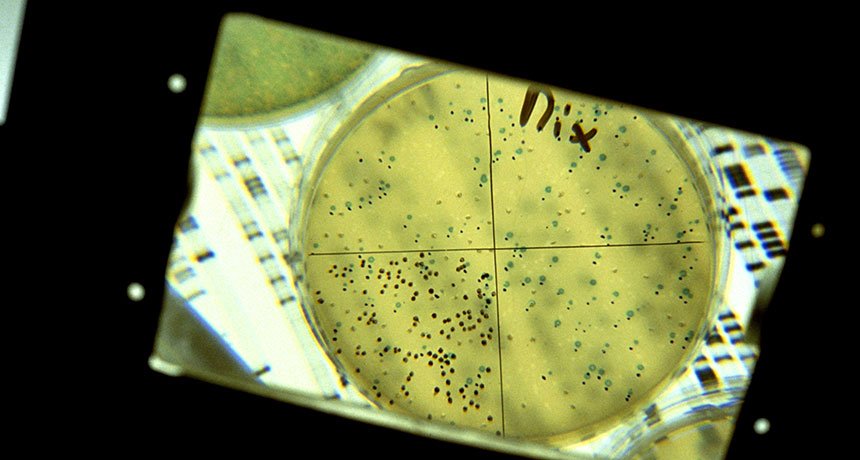

The rough, complex structures of coral reefs dissipate wave energy through friction, calming waves before they reach the shore. As corals die due to warming oceans (SN: 2/3/18, p. 16), the overall complexity of the reef also diminishes, leaving a coast potentially more exposed. At the same time, rising sea levels due to climate change increasingly threaten low-lying coastal communities with inundation and beach erosion — and stressed corals may not be able to grow vertically fast enough to match the pace of sea level rise. That could also make them a less effective barrier.

Researchers compared simulations of current and future sea level and reef conditions at four sites with differing wave energy near the French Polynesian islands of Moorea and Tahiti. The team then simulated the height of a wave after it has passed the reef, known as the back-reef wave height, under several scenarios. The most likely scenario studied was based on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s projections of sea level height by 2100 and corresponding changes in reef structure.

Under those conditions, the average back-reef wave heights at the four sites would be 2.4 times as high in 2100 as today, the team reports February 28 in Science Advances. That change would be largely due to the decrease in coral reef complexity rather than rising sea levels, the simulations suggest. Coastal communities around the world will likely see similar wave height increases, dependent on local reef structures and extent of sea level rise. The finding, the researchers say, shows that conserving reefs is crucial to protecting coastal communities in a changing climate.